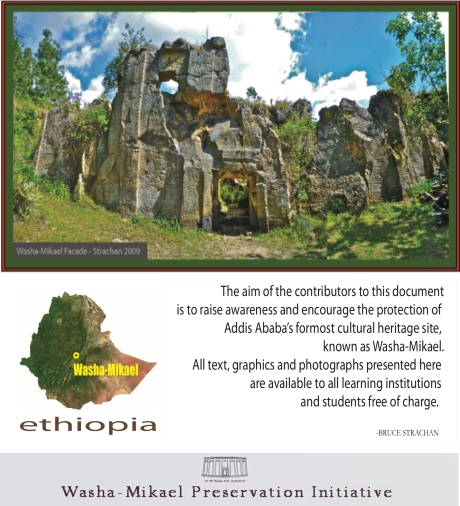

As one of Africa’s significant heritage sites the Washa-Mik’ael rock-hewn church is of tremendous historic, cultural and religious worth. Recent actions taken to concurrently excavate and protect the site are therefore greeted with enthusiasm.

The following points are inconclusive observations only, and the author very much welcomes additional constructive comment to enhance understanding:

- Reinforced-concrete foundations of a shelter are being constructed around the site. When complete this structure’s purpose would be to protect Washa-Mik’ael from the locality’s heavy seasonal rains. The success of this scheme will be determined by how effectively the structure is able to divert rainfall from the site.

- Removal of invasive root systems from structural cracks is a positive development and should protect structure from further damage in near term.

- Archeological excavation of one meter of soil at eastern edge of structure

suggests that Washa-Mik’ael’s architect’s intent was to conceive a monolithic structure – not semi-monolithic, as was earlier suspected.

suggests that Washa-Mik’ael’s architect’s intent was to conceive a monolithic structure – not semi-monolithic, as was earlier suspected. - Drainage pipe, placed at the west of the site (just beyond tunnel) may be inadequate to divert anticipated volume of rain accumulation.

- Excavation of area immediately surrounding the upright monolithic slab (north west corner of site) is reported by the site’s guide* to have uncovered human bone fragments. This information, if confirmed, seems to support speculation that the object’s function may have been to serve as a formal burial site. Best to await the forthcoming official report however as there are many layers of history associated with site. The bones uncovered therefore could have been interred during an informal phase of the church’s history.

- Since the 2011 survey new damage has been found within architectural details of the site.

While this is highly regrettable the extent is limited and the cause is indeterminable. - Findings of incomplete skeletal remains in southwest section of structure may indicate structural collapse during the construction phase.** A carbon dating examination of these remains is therefore urged, as this would likely yield reliable data as to when collapse occurred. It is furthermore advocated that a proper Orthodox burial also be performed for the remains of the deceased.

- The overall assessment of this update/report concludes that conservation progress at the Washa-Mik’ael site has been positive and should continue with compulsory caution.

Local resident and Washa-Mich’ael guide Ato Mechal reveals what are believed to be human skeletal remains uncovered in the northwest of the structure. These may hold the answer as to when the structure collapsed.

* Until an official authorised report becomes available it should be noted that while Washa-Mich’ael’s guide is an informed individual, he is not a spokesperson for the formal government sponsored excavation/conservation effort. Information provided by him or likewise this blog, while intended to be educational, is nevertheless strictly unofficial.

** It is understood that several phases of construction almost certainly occurred at the Washa-Mik‘ael site over various and prolonged periods. Until carbon dating is performed on the skeletal fragments however it remains unknown from which phase the remains in question derive.

________________________________________________________________________

Bruce Strachan has written extensively about the Washa-Mich’ael church for the Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Universität Hamburg), The Nation (Kenya), Cornerstone – the Journal of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings (London), Selamta, The Journal of the Friends of Ethiopian Studies, and the Journal of Medieval African Studies. He has also lectured on the subject at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at the University of Addis Ababa. Strachan has also appeared in a 2010 Ethiopian Television documentary citing the site’s urgent need for conservation intervention.

.

.

Positive Actions Taken To Protect Washa-Mik’ael

October 10, 2011

Update and photo by Bruce Strachan – October 2011

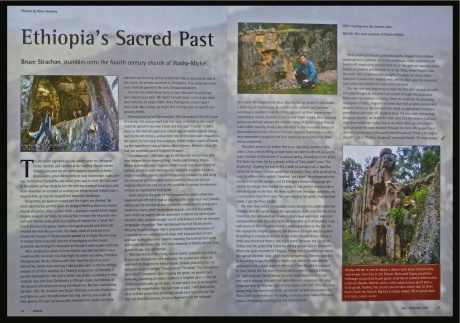

SHOA’S FORGOTTEN ROCK TREASURES

By Bruce Strachan

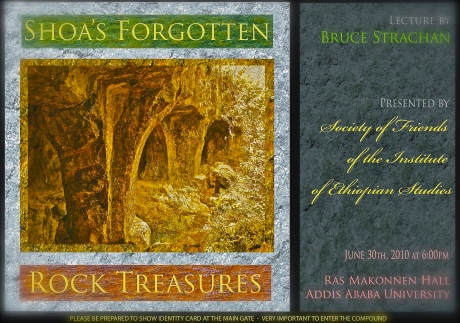

On June 30th 2010, it was my pleasure to present a discussion in Ras Makonnen Hall titled Shoa’s Forgotten Rock Treasures – this at the invitation of the Friends of the Institute for Ethiopian Studies.

Through this presentation I hoped to cast new light on medieval Shoa, a fascinating period of capitol relocation, expansion and development that came to an end when King Lebna Dengel (1507-1540) found his empire overrun by the Ottoman backed troops of a young and charismatic imam from Zeila named Ahmad bin Ibrahim al-Gazi (1506-1543).

During this faith-based conquest, known as the Abyssinian-Adal War (1528-1543), Shoa was caught early in the eye of the storm. Indeed, so widespread was the destruction of Shoa’s fine palaces, churches and monasteries that little legacy remains. So extensive moreover was the accompanying loss of life and civic disruption that Shoa’s former eminence was largely forgotten by succeeding generations. It’s not surprising then that, while knowledge of the Zagwe and Gondarian eras is relatively complete, awareness of the history of medieval Shoa, which falls sequentially in between, is lacking by comparison.

Within the vast scheme of Ethiopian* history Shoa is a relative latecomer, emerging during early stages of the Restored Salomonic Dynasty (1270-1974) founded by King Yekuno Amlak (1270-1285). Imperial relocation from Wello to Shoa during this time continued a southward trend, begun several centuries earlier with the wane of Christian Axum – a decline thought to have come about, at least partially, as a result of exclusionary trade practices introduced in the region with the arrival of Islam. Moreover, supplies of some of Abyssinia’s key export commodities, namely raw products derived from wild animals, such as elephant ivory, rhino horn and leopard pelts, may have became prone to depletion over time from within effectual range of Red Sea ports – this as demand from eastern markets, esp. Arabian, Persian and South Asian, increased.

Bruce Strachan (L) and Professor Berhanu G. Hailemariam at the University of Addis Ababa. Photo (c) Bekele Lelisho 2010

Shirazi traders, who established port city-states along East Africa’s Indian Ocean coast, and whose decedents would contribute greatly to the later hybrid culture known as Swahili, then met the bulk of these demands. In order to participate competitively in this predominantly Indian Ocean economy Abyssinian merchants were compelled to establish new southerly posts where essential commodities could be more readily accessed, and where, by means of bypassing the Red Sea, they could more directly and cost-effectively enter the Indian Ocean network of trade, via the Gulf of Aden.

Weakening revenues from Red Sea trade likely also convinced Abyssinia’s leaders to reconsider the less than optimal agricultural potentials of the north. More dependable rains and richer soils of southern highlands offered opportune alternatives, and in due course Shoa, with its exceptionally fertile land, abundance of natural recourses, and Gulf of Aden access, emerged most strategically placed.

Integral to the subsequent extension of northern culture and language, was the introduction of Oriental Orthodox Christianity with its distinctive architecture rooted in Axumite tradition. Saint Tekle Haymanot (1215-1313), born in Shoa (Selale) of Tigrayan lineage, played a particularly important role in this evangelization, during which outstanding religious and imperial sites, too numerous to catalogue in this limited report, were conceived. Notable among these is the monastery of Debre Libanos, the Debre Mitmaq Monastery (in Tegulat), the Mt Zuqwala Monastery, Managesha Hill Church and Coronation Complex, the Capital City of Barara (with it’s church and patriarchal residence), the Ginbi Church, the Semi-monolithic Church of Yeka (also called Washa-Mikael), the Adadi-Mariam Monolithic Church, The Abbo-Nebero complex, the Ejersa Church, the Enselale Church, the Kistana Cave Chapel, as well as the royal residence known as Badeqe.

Shoan Style

Ascribing one definitive medieval Shoan architectural style is not easy given that so little exemplar evidence has survived. Moreover, from a survey of remaining samples, a dynamic plurality is beheld, likely indicating much about the order and times in which these creations were conceived.

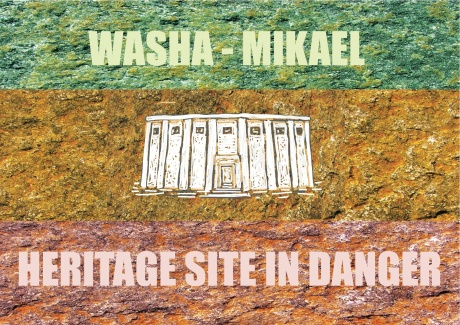

One of the earliest and finest examples of Shoan architecture is the Semi-monolithic Church of Yeka, known also as Washa-Mik’ael which, like hypogean architecture found in Wollo and Tigray, has a basilical floor plan – rather than the circum-spatium design conformity found later).[1]

Correspondingly the Yeka example also possesses nuances of Aksumite style which, as in the renowned tradition of Lalibela, expresses a certain revivalist aesthetic and sentiment.[2]

With an astonishing seven naves, and a front wall (west) measuring nearly 20 meters in width by eight meters in height, the Yeka church is exceptional for its grandeur. According to David Phillipson, only Lalibela’s Madhane Alam Church is larger.[3] Certifying such a designation is problematic however, as the Yeka Church collapsed during mid-construction due to defects in the volcanic rock from which it was hewn. Consequently it was abandoned during its present unfinished state.[4] We may of course factor in this abandonment when enquiring why this particular church escaped devastation during the Abyssinian-Adel war. Plainly, had Imam Ahmad been aware of this structure – and there is no evidence to indicate that he was, it would nevertheless have been deemed an unworthy target.

The Yeka church did not, on the other hand, go unnoticed by Menilek II who resettled the region some three hundred and fifty years later, and for whom Shoa was a land of manifest destiny. Menelik took active interest in rehabilitating the Yeka site by adding the built up stone structure nearby, of which only the foundation and steps remain. Perhaps more fascinating however is that earlier ruminants – contemporaneous to the earlier era, appear beneath and around Menelik’s structure. The semi-monolithic Church in Yeka appears therefore to have been but one of several components within a larger complex.[5]

Although incomplete, the grand ambition expressed within the proportions of the Yeka project suggest that was an undertaking of considerable cost. It is likewise significant to find clear revivalist elements of Aksumite architecture this far south, where no other such comparable examples are known.[6]

Some forty kilometres south of Yeka, the Adadi-Mariam church qualifies as the more southerly example of monolithic architecture. However, a centrally placed Makdas suggests that this building chronologically followed the Yeka example. There are moreover quality and size distinctions between the Adadi-Mariam and Yeka Churches, which in the final analysis accord greater significance to Yeka.[7]

About 15 k east of Adadi-Mariam, along the north bank of the Awash, a most astonishing complex of six architecturally enhanced grottoes, known as Abba-Nebero, appear. Upon inspection of this assemblage, Richard Pankhurst wondered if it might not have been the ‘Monastère de Notre Dame,’ from the ‘palace of the Kingdom of Gorage,’ as described by Alveraz[8].

A curious, squared object with a cubical-shaped hallowed out niche, has been hewn from the living rock in the centre of what appears to be the complex’s principal chamber. This approximately one and a half metre-tall object, is aligned on a precise north-south axis, and almost certainly served an ecclesiastical purpose – possibly having once been a type of Holy-of-holies in which a tabot might have been kept. Religious function of the site seems therefore without question. Otherwise, architectural details found throughout the various chambers are eclectic, with informal additions such as wall recesses, possibly added during the post-conquest centuries of abandonment.

Of particular interest is a distinctive adornment above one of the primary entrances, consisting of two hollowed-out orbs carved into the wall above each door corners. Reservoir areas for oil, and residue of soot may be observed on the roof of each orb, suggests that these features may have served as oil lamps.

The space between is accentuated by a recessed horizontal element, instantly recognisable as a configuration, matching the arrangement found above the west door of the afore mentioned semi-monolithic church in Yeka. Notably the horizontal element in the Abba-Nebero example is arched, whereas the Yeka version is straight. Otherwise the designs are identical and demonstrate a significant, uniquely Shoan correspondence in style.

The 2,989 meter high monastery on Mount Zuquala, founded by St. Gebre Manfas, was destroyed and looted at the outset of the Abyssinian-Adel war. What remains of the original structure has been duly sealed under a bed of cement that presently constitutes foundations of the present Kidane Mihret Church (constructed during Emperor Haile Selassie’s time). The far-reaching celebrity of Mt. Zuquala is highlighted by its having appeared in various medieval documents such as Fra Mauro’s 15th century Mappamundi.

Likewise Imam Ahmad’s forces destroyed the Managesha Hill Coronation Complex, commissioned by Zera Yakob – an extensive site that seems a highly probable candidate to be the Amba Negast (King’s Mountain) indicated on Fra Mauro’s Map. And may, if confirmed, be a highly useful clue in determining the location of the lost imperial capitol city of Barara (placed by Mauro directly west of the Amba Negast.)[9]

References to Barara such as these, as well as those of 16th century Venetian man of letters Alessandro Zorzi,[10] provoke the imaginations of researchers. Surely the most poignant such references however come from Imam Ahmad’s own loyal war-chronicler – a Yemeni named Arab Faqih who in 1531, after witnessing the city’s pillage first-hand, cataloged the events in Volume I of his, Futuh al-Habesa (Conquest of Ethiopia).[11]

Various clues are immediately appreciable from these sources, such as the map’s geographical orientation between Barara and Mt Zukwala. Other clues prove less decipherable. Still others seem utterly contradictory.

For instance, two separate sources within the Futuh al Habesa cite the number of days a traveler might allow to complete the trek between Debre Libanos and Barara by foot – information that, because Debre Libanos was a pilgrimage destination, we may assume would not have been uncommon knowledge.

The first of these sources, an unnamed Barara citizen, stated that the journey would require a 6-day ‘march.'[12] Subsequent testimony however, coming from one of the Imam’s lieutenants, emir Abu Bakr Qatin – whom the Imam dispatched to pillage the monastery, related that the return march had taken he and his men 12 days.[13]

This inconsistency however, may be reconciled when taking into account that, unlike a lone traveler, Abu Bakr Qatin and his over three hundred strong foot-soldiers would’ve been encumbered, not only by a militia’s logistical constraints and bulky weaponry, but moreover by having to also haul the prodigious volume of booty seized from the monastery.

In their well researched 2009 Annales d’Ethiopie essay, Barara, the Royal City of 15th and Early 16th Century Ethiopia, Professor Richard Pankhurst and Hartwig Breternitz chose Mt. Yerer as the northern boundary of the zone, within which they reasoned Barara’s ruins were likely to be found.

“There is sufficient evidence to locate it [Barara] in the area between the Wechecha Range and the Akaki River in the west, Mt Yerer to the North, Mt Ziqwala and the Awash River to the south and the Mojo River/Debre Zeyt to the east.”[14]

My own research findings largely conform to this assessment. However, I remain open to the possibility that the search zone might be extended north, beyond the Mt Yerer boundary proposed by Pankhurst/Breternitz.

This estimation is based on clues found in the Fra Mauro Map, as well as the ‘six-day march’ clue found in the Futuh al Habasa. In order to test the later clue I set out by foot in 2009 to determine how far an average individual could trek from Debre Libanos in the six days cited by the individual from Barara.

From Debre Libanos my colleague Ato Jalata Kagela and I followed a relatively straight southward route, over earthen paths and across high open plateau, roughly parallel to the highway known as Dese Road. Averaging approximately 20km per day we arrived, on the 6th day, in the city centre of Addis Ababa. Had we continued hiking at this pace for 12-days (number taken by Abu Bakr Qatin to reach Barara), we might well have wound up at Lake Koka – 20km south of Mt Zukwala – well beyond the reasonable research zone.

Although inconclusive, the result of this test – along with continued scrutiny of other primary source evidence, leads me to strongly consider that the twelve-day scenario is indeed based on unusual circumstances – and that the six-day scenario is therefore the more reliable indicator. Based on the result of this experiment the Barara search zone therefore, might well be extended northward – beyond Pankhurst/Breternitz’s limit of Mt Yerer, to also include what are today the eucalyptus covered range of hills known as Entoto where indeed, vast and substantial medieval ruins do lay scattered.

Three hypogean sites hewn from minor deposits of rose volcanic tuff are found in close proximity to the 19th century Church of Saint Raguel. According to tradition these were churches that date back to the reign of Dawit II – a.k.a., Lebna Dengel (1508–1540). This tradition might prove highly significant as Dawit II, who is on record as having had a palace in Barara, was emperor during Barara’s 1529 sacking.[15]

Until further research is conducted it perhaps can’t be entirely ruled out that these hypogeum might once have been churches – particularly the most formal of the three. It seems prudent however to not also consider that they – the two relatively small and rudimentary rock-hewn sites in particular, might have performed different functions – possibly as storehouses.

That these particular structures support theory that Entoto is the location of the lost capitol of Barara is weak. Firstly because these modest chambers, in and of themselves are not particularly outstanding, nor do they correspond in any way to what is described by the primary evidence.

The Futuh al-Habasa records that the imam’s men destroyed Barara’s ‘great’ church and palace utterly.[16] Therefore when searching for Barara’s remains one must expect to find a highly distressed site. If these minor hypogean premises are to be factored in as evidence therefore it could be secondary at best. And if one were to pursue them as such it would seem practical to wonder therefore, what might lie beneath the foundations of present built-up structures in that locality. It is after all, not unusual for incoming civilisations to build upon foundations of the outgoing.

Vastly more compelling than these three hypogean sites are the various medieval-era wall fortifications, found in various condition, throughout Entoto (and Yeka).

When initiating settlement of Ethiopia’s modern capitol Addis Ababa, Emperor Menelik II acknowledged the imperial medieval history of Entoto, which he accorded to Dawit II. Indeed it was under that pretext that the emperor chose this specific location upon which to construct his own palace and church.[17]

Rich cultural heritage as such undoubtedly energized what was then an expansionist mandate based largely upon the principal of re-claiming lands and sites lost or destroyed as a consequence of Ethiopia’s turning point – remembered as the Adel-Abyssinian War.

Imam Ahmad’s army also destroyed the Ginbi-Tewodros Church atop Mount Yerar as well as the nearby fortified city today known as Sire,[18] which may represent remains of the Medieval Town indicated as Mason, on the Mauro Map and in the Futuh al-Habasa.

Architectural design elements found in the Ginbi-Tewodros Church, and likewise Ejersa and Enselale, demonstrate departure from previous style. The introduction of this new elegance and inventiveness, probably dates to the late 15th or early 16th century.[19] Stylistic incorporations, such as nautical style doorframes and window trim, as well as panels intricately carved with cruciform motifs, are not wholly unlike certain dressed stone elements found in the Gondarian architecture, which followed. An untilled, but highly promising area of comparative research awaits exploration here.

Location of the Battle of Shimbra Kure ‘Chickpea Swamp (or seasonal lake),’ fought between Adal forces led by Imam Ahmad and the Ethiopian army, under Dawit II (Lebna Dengel in March of 1529).

Of Shoa’s numerous medieval sites none is more charming than the Kistina Cave Chapel, found in relative proximity to Adadi Mariam. This tiny enhanced cave is one of very few examples of medieval Shoan architecture to have survived largely intact – due, no doubt, to it’s particularly secretive location and disguised entrance.[20]

The whereabouts of the city of Badeqe is also as yet one more Shoan mystery waiting to be deciphered. Arab Fiqah informs us in his Futuh al-Habasa, that the church of Badeqe was commissioned, ‘in a most beautiful fashion,’ by King Na’od’s wife Sabla Wangel, and with this piece of information we can reliably fix the church of Badeqe to the early 16th century.[21]

Portuguese emissaries had by this time, already appeared on Shoan soil offering skills, while promoting, with limited success, their Roman Catholic version of Christianity. This diplomatic mission, led by Pero da Covilha, proposed a strategic alliance designed to defend against the imminent Ottoman-backed Adel threat, based largely upon the two distant nation’s general commonality of faith. Not seeing, at the time, sufficient benefit from such a partnership, the young Emperor Lebna Dengel declined.

Formal alliance or not, simply the hint of association between Abyssinia and the Portuguese must have been provocative to neighbouring Muslims who, in the larger regional picture of Portugal’s increasingly assertive presence on the Indian Ocean, viewed Portugal’s intent as one of forcibly broadening its share of Indian Ocean trade. Hostilities had escalated shortly before with Portugal’s second bombardment of Ziela (1528) – hometown of imam Ahmad.

The King’s ‘village’ of Badeqe meanwhile, was a sitting target, and in the aftermath of the decisive Muslim victory in the Battle of Sembera Kore (1529), Arab Fiqah fatefully recorded the following:

- “The imam [Amhad] said to his companions, ‘Now that God has given us the victory over them, and has humiliated them [in the Battle of Sembera Kore], let us march on Badeqe the place where the king’s residences are, to take him and to demolish it. Let us occupy Abyssinia, conquering the country and weakening them.”[22]

Emperor Lebna Dengel lived to fight another day, but Shoa was defeated and imam Ahmad’s momentum forced him to flee north. Thus another page in Ethiopian history turned.

Conservation

Most of the sites discussed in this report are at urgent risk of further damage due to natural erosion and or human interference, particularly from residential expansion, farming and rock quarrying. It’s hoped however that by raising public awareness conservation measures may be advanced.

How to proceed raises questions without simple answers, especially for a developing nation with other pressing priorities – this compounded by the reality of being so endowed with abundance of important sites in need.

I am nevertheless convinced that application for UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites In Danger List, on behalf of these monuments, must be put forth as a successful lobby would gain a significant portion of the much needed financial support.

More research and analysis lies ahead before a meaningful portrait of medieval Shoa may be attained with desired realism and clarity. But we should take immense satisfaction in that the subject is unquestionably worthy. We are furthermore encouraged that so many distinguished members of the community attended the Shoa’s Forgotten Rock Treasures presentation. This turnout is a positive indicator of public wakefulness and we furthermore heartily appreciate the pledge made on that occasion by the Honourable Minister of Culture Mohamed Derir with regards to the Yeka church, for which we have already begun to see implementation.

In closing let me state that this survey could not have been carried out were it not for the input and support of people unto whom special recognition is owed – namely, Dr. Jacinta Muteshi, Ato Jalata Kagela, Dr. Berhanu G Hailemariam, Dr. Shiferaw Bekele and Dr. Richard Pankhurst.

Bruce Strachan is a Nairobi based artist and writer who resided in Ethiopia between 2001 and 2004 – and then again in 2010-11. He has written about medieval Shoa for various publications including Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, The Nation, Cornerstone – Journal of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, and Selamta – magazine of Ethiopian Airlines.

* In the context of this report the term Ethiopian is used to include all civilisations (such as D’mt and Axum) which, although recognised by other names, occurred within the boundaries of what is presently defined as ‘Ethiopia’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANFREY, Francis, Enselale, avec d’autres sites du Choa, de l’Arsi, et un ilot du lac Tana, Annales d’Ethiopie, Vol. XI, 1978.

ANFREY, Francis, Des Eglises et des Grottes Rupestres, Annales d’Ethiopie, Vol. XIII, 1985.

ANFREY, Francis Autour du Vieil Entotto, Annales d’Ethiopie Vol. XIV 1987.

BECKINGHAM , Charles F. and HUNTINGFORD, George B. W., The Prester John of the Indies, Cambridge, 1961.

BRETERNITZ Hartwig & PANKHURST Richard, Barara, the Royal City of 15th and Early 16th Century Ethiopia, Annales d’Ethiopie, Vol. XXIV, 2009.

BUXTON, David, The Christian Antiquities of Northern Ethiopia, London, 1947

CASTRO, Lincoln de, Nella terra dei Negus, Milan, 1915.

CRAWFORD, O.G.S. (Edited by), Ethiopian Itineraries circa 1400-1524. Cambridge, 1958.

DERAT, M.L., Le Domain des rois éthiopiennes (1270-1527). Espace, pouvoir et monarchisme, Paris, la Sorbonne. 2003.

DORESSE, J., Ethiopia. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, London, 1959.

GODET, Eric, l’Eglise et les Habitations Rupestres du Vallon de Kistana, Annales d’Ethiopie, Volume 10, 1976.

HENZE, Paul, Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia Hurst and Co. London

HUNTINGFORD, G.W.B., The Glorious Victories of Amda Seyon, King of Ethiopia. Oxford University Press, 1965

HESPELER-BOULTBEE, J.J. A Story in Stones, CCB Publishing, 2011.

LEPAGE, Claude, L’eglise Rupestre de Berakit, Annales d’Ethiopie, Vol. IX, 1974

MATTHEW, Austin Frederick, Canon, The Monolithic Church of Yekka, Journal of Ethiopian Studies, VII, 1969.

MONNERET DE VILLARD, Ugo, La Chiesa Monolitica di Yakka Mika’el. Rome, 1941.

MUNRO-HAY, Stuart. Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991.

PANKHURST, Richard, Caves in Ethiopian History, with a Survey of Cave Sites in the Environs of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Observer, XVI, 1973.

PANKHURST, Richard, A Cave Church at Kistana, Ethiopia Observer, XVI, 1974.

PANKHURST, Richard, The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles. Addis Ababa: Oxford University Press, 1967.

PHILLIPSON, David W., Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, New Haven, 2009.

RAMOS, M.J. & BOAVIDA, I. The Indigenous and the Foreign in Ethiopian Christian Art. Ashgate, 2004.

RICCI Lanfranco,Resti di Antico Edificio in Ginbi (Scioa), Annales d’Ethiopie Vol. X 1976.

ROCHET DE HÉRICOURT, Charles-François-Xavier, Second voyage sur les rives de la Mer Rouge, dans le pays des Adels et le royaume de Choa (Paris, 1846).

SAUTER, Roger, L’Eglise Monolithe de Yekka-Mikael, Annales d’Ethiopie, Volume 2, 1966.

STENHOUSE, P.L., Futuh al-Habasa: The conquest of Ethiopia, (by Sihab ad-Din Ahmad bin Abd al-Qader bin Salem bin Utman),with annotations by Richard Pankhurst. Hollywood: Tsehai, 2003.

STRACHAN, Bruce, Ethiopia’s Sacred Past, Selamta, Addis Ababa 2008.

STRACHAN/PANKHURST, Dr. Richard, The Semi-monolithic Church in Yeka – Heritage Site in Danger, Annales d’Ethiopie, Forthcoming.

TAMRAT, Taddesse. Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270 – 1527. Oxford University Press, 1972.

ENDNOTES

[1] Sauter (1966), pp., 15-36.

[2] Phillipson (2009), pp., 119-121.

[3] ibid.

[4] Matthew (1969), pp., 89-98.

[5] Strachan/Pankhurst (forthcoming).

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] Anfrey (1985), pp., 7-34

[9] Breternitz & Pankhurst (2009), pp. 209-249

[10] Crawford (1958).

[11] Stenhouse, P.L. (2003).

[12] ibid.

[13] ibid.

[14] Breternitz & Pankhurst (2009), pp. 209-249

[15] Stenhouse, P.L. (2003).

[16] ibid.

[17] SELLASIE, Guebre. Chronique du Regne de Menelik II. Paris, 1930, Vol. 1, p163.

[18] Ricci (1976), pp. 177-210.

[19] Anfrey, (1978), pp., 153-178

[20] GODET, Eric, “L’Eglise et les Habitations Rupestres du Vallon de Kistana,” Annales d’Ethiopie, 1976, Volume 10, pp. 145-156.

[21] Stenhouse (2003) pp., 58

[22] ibid.

.

.

.

*

The Ministry of Culture began efforts last week to preserve the semi-monolithic church in Yeka, called Washa-Mikael – this according to a very pleased and excited sounding Ato Amiro Wubante. According to Amiro, a guide at the site, work has begun to clear away flora overgrowth and dig a trench to allow rain drainage and avoid flooding.

Bruce Strachan – Nairobi/January 22nd, 2011

*

New Vandalism Found At Addis Ababa’s Foremost Heritage Site

November 12, 2010

By Bruce Strachan

Nairobi,

3, Hdare 2003

Worsening of structural integrity due to continued root invasion has once again been monitored at the semi-monolithic church in Yeka. Why this resolvable problem is permitted to continue ravaging a monument of such significance vexes many, but today what is particularly disturbing is that another, new sort of unnatural damage is now beginning to appear – human vandalism.

Two cavities, one 3.5cm and the other 2.75cm in diameter, have been bored into the convex spherical detail, just above the upper-right corner of the west door, marring the structure’s focal design element. Unmistakably man-made, this new vandalism was first seen on November 3rd (24 Tekemt 03), and was not present during a previous photo documentation of the site three months ago.

Graffiti has long been a nuisance for this site popularly known as Washa-Mikael. In addition to these written inscriptions, hermits and squatters have also added their own personal touches down through the ages. A crude ladder leading to a window was carved in the exterior of the south wall, as were small interior niches and basins. But unlike these vintage ‘home-improvements’, the new damage appears to be vandalism purely for vandalism’s sake.

Thanks to recent efforts to raise greater public awareness and generate a conservation mandate the Yeka church was listed as state inventory in 2010 – first step towards application for World Heritage Sites in Danger nomination. Recognition from UNESCO could bring critically needed financial support, not just to protect this particular site, but to a group of prominent Shoan sites in danger, believed to date back to the medieval era dynasty of Yekuno Amlak*.

Such a ‘Southern Historic Route‘ would have potential to generate important dividends from cultural tourism while at the same time safeguarding Ethiopia’s National Heritage.

*The Ethiopian Orthodox Tawahedo Church states that the Yeka church was built by Abreha and Atsbeha during the fourth century Dynasty of Menelik I.